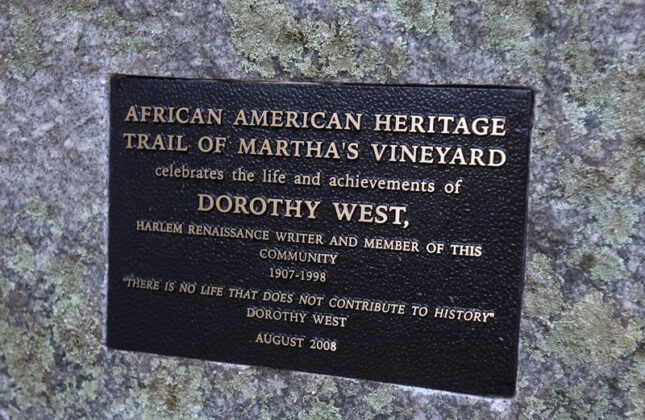

When we think of the Harlem Renaissance, names like Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Zora Neale Hurston usually spring to mind first. But there’s one name that deserves just as much recognition: Dorothy West. Her gravesite Oak Bluffs is marked as the “last leaf of the Harlem Renaissance,” and rightfully so. West played a crucial role in preserving the legacy of this vibrant cultural movement, ensuring that the contributions of its literary talents were neither lost nor forgotten.

The Harlem Renaissance, a jubilant celebration of Black creativity and cultural resurgence spanning the 1910s to the 1930s, was a transformative period that shaped the African American perspective in the arts globally. It was a time when the syncopated rhythms of jazz mingled with the vibrant hues of visual art, and the lyrical poetry of Langston Hughes danced alongside the prose of Zora Neale Hurston.

In 1940, West’s literary talent garnered recognition when Dorothy tied with Zora Neale Hurston for second place in a prestigious contest sponsored by the Urban League’s Opportunity magazine. This pivotal moment served as a catalyst for West, propelling her towards the bopping streets of Harlem, where she would embark on her own literary journey.

West’s journey to prominence was marked by resilience and determination. She was born to Isaac West, who found freedom from slavery following the passage of the 13th amendment, and Rachel Benson West, whose lineage traced back to the Gullah Geechee culture of South Carolina, Dorothy’s upbringing was imbued with a sense of determination and pride. Her father started a fruit company after he was liberated and became known as the “Black Banana King” of Boston. At the tender age of 14, West published her first short story, “Promise and Fulfillment,” for the Boston Post. She would go on to study at Boston University and Columbia University.

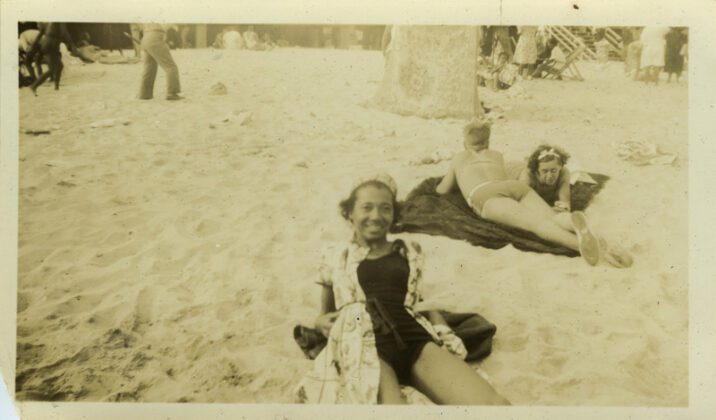

Her writing would take her to Russia, and it wasn’t until Dorothy learned of her father’s passing that she came back to the United States and decided to live on the Vineyard permanently with her mother in their family home. As a staple of Oak Bluffs and a titan for education, Dorothy was often invited to speak at colleges and universities and to students all over. Retired professor and Edgartown resident Dr. Lorna Andrade recalls a time when she invited Ms. West to speak at an assembly at Massachusetts Bay Community College, and she had to interrupt Dorothy’s talk to give her a lift because she was so short and had to speak over the podium. Andrade recalls: “She was a force to be reckoned with, although she was petite. She had a mighty presence.”

Another recollection comes from Stephen R. McDow ll, Oak Bluffs resident and heir to the artist, educator, and advocate Delilah W. Pierce Collection. “When I was a child on the Vineyard we would always visit the Bonaparte’s home on Narragansett for one of their seafood dinners. I recall Dorothy came over to sit on the porch and later moved in with us for dinner. Everyone who knew them always LOVED the Bonaparte’s seafood salad and stuffed baked seafood imperial and this time didn’t disappoint! Since Aunt Louise was one of the founding members of the Cottagers, she, Dorothy, and the Bonaparte’s talked for hours about Island gossip, the arts, and education — always asking me about how I was doing in school and to leave the girls to after I got my education!”

With a razor-sharp mind and a penchant for adaptability, Dorothy navigated a landscape where opportunities for Black women artists were scarce, and recognition was hard to come by. In a world where the red carpet wasn’t rolled out for Black creatives — especially women, Dorothy found herself grappling with a system that often overlooked her talents, deeming her work not “Black enough” for mainstream publication — a struggle that resonates with many contemporary writers facing similar challenges in a rapidly evolving media landscape.

Publishers and editors, bound by narrow perceptions of what constituted “Black literature,” refused to champion her work. Undeterred, Dorothy took matters into her own hands, and with $40 she launched “Challenger,” a magazine born out of necessity and fueled by her desire and determination. Despite facing criticism and a short-lived run, “Challenger” served as a poignant reflection of its era, embodying the struggles and aspirations of its creator. Undeterred by setbacks, Dorothy West attempted to breathe new life into the magazine in 1937 with the aptly named “New Challenge.” However, in an attempt to align with the political climate of the time and appease figures like Richard Wright, the revived zine met a similarly brief fate. Despite its brevity, “New Challenge” left a historic mark, its influence reverberating through the literary landscape and serving as a touchstone for future generations of artists and activists.

Her first novel, “The Living Was Easy,” published in 1948, was written in her East Chop cottage. which is included in the Martha’s Vineyard African American Heritage Trail. At this time she was a regular columnist for the Vineyard Gazette and wrote short stories for the New York Daily News, becoming the first Black writer to do so under the federal writers project. This was possible due to her agreement that she would avoid references to her race.

Diana Evans of The Guardian stated that West wrote “posh black” at a time when “broke black” was in vogue. It was a chance encounter with Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis on Circuit Avenue that altered the trajectory of West’s career later in her life. Onassis, an avid admirer of West’s column in the Vineyard Gazette, recognized the inherent brilliance within her words. This fortuitous meeting ultimately led to the 1995 publication of West’s acclaimed novel “The Wedding” by Doubleday, shifting the course of her literary career.

Dorothy West’s journey as a Black woman writer and artist is something of awe. From her early inspiration from Fyodor Dostoevsky to her pivotal role in the Martha’s Vineyard’s cultural scene, she defied societal barriers. Despite facing obstacles both in the U.S. and abroad, she continued to find creative solutions to her problems, she co-founded magazines like “Challenger,” penned acclaimed novels like “The Wedding,” and became a voice for her community through columns and contributions.

As we reflect on the historical legacy of the Harlem Renaissance, let us not forget the dynamic spirit of Dorothy West, whose unwavering commitment to Black literary excellence continues to

inspire and uplift generations. Her influence extended far beyond our Island shores. She may have been the “last leaf,” but her legacy remains evergreen, a testament to the enduring power of Black creativity and resilience.

Nydia Simone is a versatile local storyteller and curator who passionately uses various mediums to share nuanced narratives about the African diaspora worldwide.