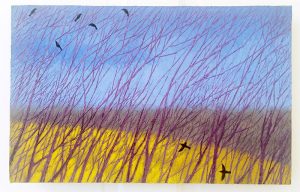

“May Wall,” oil on board, 26 x 36 inches, 1988. Paintings: Stan Murphy.

You open the door and walk right into a large landscape, “Winter Sunset,” painted by Stan Murphy in 1960. It’s an odd landscape; it takes time and study to read. Is the cadmium red top third of the painting supposed to be sky? Or ground? It has blue and ocher scumbled and drawn into that red surface. Are they grasses? Or just the artist’s way of breaking up that expanse of red? It’s a bird’s-eye view, looking down on that snowy ground, that the birds and grasses, the darkly drawn puckerbrush, were all right below and ambiguous. The painting is rough and almost cartoonish compared with the intricately drawn and smoothly rendered later landscapes, but it has its appeal. None of his children ever remember seeing it before.

That was my introduction to “Landscapes, Nudes, and a Bit of Fancy,” the second Stan Murphy retrospective curated by Nancy Kingsley at Featherstone Center for the Arts. Last year’s exhibition featured his portraits. Afterward, people kept coming up to Nancy to tell her about the Stan Murphy painting(s) they had, all different subjects and painted at different stages of Stan’s career. There was enough to fill the gallery again, and that’s what Nancy, gallery director Ann Smith, and gallery manager Kate Hancock decided to do.

It is a wonderful show. It is always a gift to see a continuum of an artist’s work, to see the development of subject matter and craft, also to see so many paintings from private collections that one would likely never have the opportunity to see otherwise.

The earliest painting is of Katharine Cornell’s home, “Chip Chop,” painted in 1949 after Stan knocked on her door asking if she would be interested in having him paint a portrait of her house. She was, and she became a lifelong friend and patron.

“Menemsha Creek” is another large landscape painted in 1957. Like “Winter Sunset” it maintains the loose brushwork, straight up and down, flattening the perspective of three large sloping shapes of grassy dunes that make up most of the composition. Patches of blue and pink marks are worked into the overall ocher or Naples yellow that colors the dunes; those marks keep the viewer’s eye focused on the flattened shapes, rather than shooting down the slope and out of the painting. The edges where one section meets another are softly brushed. Across the top, a flock of white birds flies in a calligraphic flutter, while watery waves mimic that effect across the bottom.

Three little oil sketches on board, quickly painted to capture the effects of sunsets that appear and disappear in a matter of minutes, were so loose and fresh. They were painted in 1980. By then, Stan’s landscapes had developed into what I would describe as “a Stan Murphy painting.” The drawing is tighter and more complex, the color values closer, making the viewer really look to discover all that is within the large shapes of tree lines or water or fields. The paint is thinly applied, and the subjects are at once dramatic and serene.

“May Wall,” dated 1988, shows a close-up of a stone wall, lichen-covered, with daffodils with yellow petals and orange cups coming up through a dead, brown oak-leaf-littered foreground. The painting is smoothly polished and offers an invitation to slowly and completely immerse yourself in discovering subtlety after subtlety. A painting shouldn’t be seen all in one glance.

There are lots of drawings in this show. My favorite was a large sheet of paper with pencil-drawn sketches of Laura Murphy when she was a small child. Drawings are, to me, the most personal of an artist’s expression. Many of the large nudes were carefully rendered and quite polished. I have seen many of Stan’s drawings over the years, mostly studies for paintings. They always have the feel of his hand.

I can’t get a painting of Polly, Stan’s wife, out of my head. It’s small. The description said it had been cut down from a full-length portrait. She has her head turned away, just a profile, her hair piled up on top of her head, the drawing still visible in many places, a soft gray-blue defining the edges of her face and head. It is one of the most beautiful portraits I have ever seen.

The nudes in this show, as the landscapes do, range from early works of thick impasto and inventive color patterns to smoother, more modeled, thinly painted figures on glowing surfaces. Mixing his colors with medium makes the surfaces shimmer. Bits of underpainting and drawing are left to soften some of the edges, while others are sharply delineated.

Stan had a wonderful sense of humor, and his 1971 painting “Muse” shows it off perfectly. There is Stan at his easel in the lower left-hand corner, while towering over him and filling most of the painting is a wild-looking nude, arms akimbo, demanding to be noticed and attended to.

Walking around for a couple of hours, talking with Ann, Kate, and Nancy, then being left to myself, I was able to really observe the paintings in an unhurried way. As I said earlier, paintings shouldn’t be taken in all at once. Stan had layers and layers to himself, and it was a gift to slowly savor some of the layers he left to be discovered in his art. His landscapes are nostalgic, scenes that may no longer exist, and his nudes depict women forever young and ripe. Besides the images, there was, for me, the technical and visual refining over an artist’s long career.

This story by Hermine Hull was originally published in the MV Times.