In July 1893 the Boston Globe reported the opening of a new hotel on Martha’s Vineyard “called by the ultra-fashionable name of Makonikey Inn, which is situated on the highest ground of Makonikey hights.” A corruption of the Wampanoag name “Conaconaket” (“ancient place”), Makonikey marks an ancient boundary dividing the area once known as Chickemmoo, and today marks the town line between Tisbury and West Tisbury on our north shore. Surrounded by rich clay deposits, it was the site of a brick kiln in 1700.

The fancy new three-story hotel, funded by a syndicate of off-Island capitalists, featured 20 rooms, four dining salons, and a laundry. A bathhouse offered guests a choice of fresh or salt-water bathing in porcelain tubs, in addition to an expansive beach on the shore below. It was the first hotel on the Island with an electrical generator, and each room was equipped with its own electric light. Four or five cottages were built on a labyrinth of newly graded roads, and lots for another 200 were put up for sale. A 200-foot wharf met guests debarking steamboats from Woods Hole and West Chop, and a survey was even drawn up for a new road to connect Makonikey directly to West Chop.

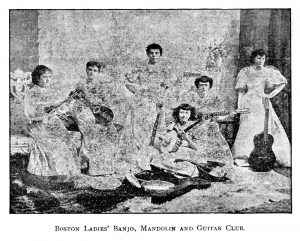

The opening was a grand success. The hotel hired the Boston Ladies’ Banjo, Mandolin and Guitar Club for the season’s entertainment — an ensemble led by Mrs. Helen Friend-Robinson on the banjeaurine, banjo, mandolin, and guitar, and featuring child prodigy Maudie Scott.

But 1893 turned out to be a terrible time to open a hotel. The economic crisis known as the “Panic of 1893” crippled the national economy, and when the time came five weeks after the hotel opened to pay the 16 Italian workers from New Bedford who had just finished grading the hotel grounds, the contractor who hired them skipped town. Out of both money and food, the workers stormed and occupied the lobby of the new hotel, and threatened to burn it down unless payment was forthcoming. It wasn’t. The guests panicked.

Henry Beetle Hough, in his 1936 book “Martha’s Vineyard Summer Resort” described the scene: “In the still darkness, a file of frightened people emerged from the hotel and took flight toward Vineyard Haven, some of them partly dressed, some dragging suitcases and other belongings, some leaving almost everything behind. Their ankles torn by briars and bushes, the guests cut across fields and through thickets, not pausing to feel out paths or roads. The stragglers reached Vineyard Haven at last and were received and sheltered.” They departed on the morning boat. Meanwhile, the furious workmen refused to leave.

“Italian Workmen at Makonikey Hights Demand Their Pay or the Blood of Their Employers” read the headline in the Boston Globe the next day. The hotelkeeper, George Q. Pattee of Somerville, hired eight armed men from Cottage City as a private police force to guard himself, and a handful of (also unpaid) servants from the mob of angry men who spoke almost no English. Tension was abated somewhat as Pattee’s servants fed the workers from the hotel kitchen. “The sympathies of the people around the town are altogether with the unpaid employees,” reported the Globe, noting that the workers lacked the funds to even leave the Island.

While the end of the standoff was not reported, it was a death knell for the hotel. It may have reopened briefly under new management the next summer, but it never found its footing again. In 1897 it was sold at auction. From 1913 until 1919 the YMCA used the aging premises as a summer camp, and during the Great Depression, squatters were said to have taken residence in the abandoned hotel building. In 1932 a party of young people sailed over from Woods Hole to play “murder in a haunted house,” only to be detained by the State Police to face charges of destruction of property. (They paid $700 in a settlement.) The building was still (mostly) standing as late as 1936.

Over the years the cottages were sold and moved, and the hotel was slowly dismantled by neighbors and opportunists. Lawyer Charles Brown is said to have purchased a number of the cottages and moved them to Vineyard Haven, where many still stand today. Nothing remains of the Makonikey today but a few traces of the foundation and, it’s reported, a couple of porcelain bathtubs.

Chris Baer teaches photography and graphic design at Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School. He’s been collecting vintage photographs for many years.